Natural Consciousness in "Russia!"

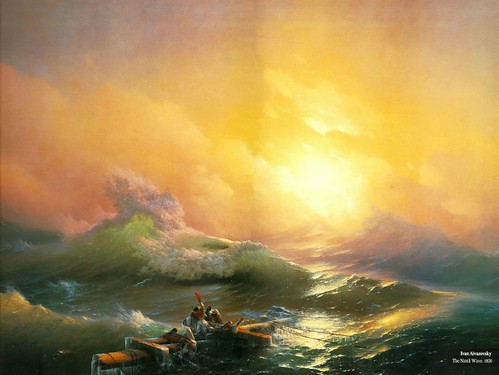

Ivan Aivazovsky, The Ninth Wave, oil on canvas, 1850

“I assure you, gentlemen, that to be too acutely conscious is a disease, a real, honest to goodness disease.” – Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Notes from the Underground, 1.2, 1864

Looking at the restraints placed on Russian artistic consciousness, seen in the Guggenheim’s “Russia!” one cannot help experiencing a weary exhaustion, taking up the struggles for expression and a hyper-aware national identity as so many peasants labored over the unending expanse of the oppressive motherland. In nature, Russian artists find a subject capable of tempering and challenging the force of totalitarian rule, as well as a source of inspiration to endure the bleakness of social currents and political turmoil.

How can something so beautiful and uncorrupted as the landscape of

Throughout the history of Russian art presented in this show – inextricably viewed in the context of national political and cultural history – a plague of suppression and subversion of identity spreads. Whether struggling to keep up with the French under Catherine the Great or attempting to work within the strict confines of Socialist Realism as mandated by the Communist Party, Russian artists have often faced an officially-prescribed doctrine of thought and agenda of visual culture. A

Some of the most successful answers come in turning to nature, an indigenous path which arose in the late 17th century icon painting – artists sought and found a space to ask questions, a terrain for thought, a place to project outrage or confusion, or even a force greater than any politics of man. Ivan Aivazovsky’s The Ninth Wave (oil on canvas, 1850) is an unsettling, dramatic and tempestuous scene of men hopelessly clinging to the mast of a sunken ship amidst colossal surging waves in the eerily beautiful sea back-lit to gorgeous transparency by an ambiguously eventful pink and yellow sky such as one may dream of in a vision of the heavens, either the most welcoming sunrise after the treachery of a night in turmoil or, more likely, the departing rays of a seductive and rapturous sunset sure to be the last vision of earthly beauty emblazoned on the minds of men about to be abandoned to the tortures of the night and certain death. This visage of man’s struggle is as horrifying as it is captivating, incorporating the most moody and awe-inspiring aspects of Romanticism with the wholly Russian introspection of a prescient self-awareness, a national consciousness drowning in its own tides of change and unrest, carrying all the weight of history against an airy optimism for the future, the fervent faith in spring which surely makes survival through the winter even remotely possible.

The undeniable and unequivocal importance of nature and the land – either as prison or salvation for the spirit – most poignantly surfaces as a status indicator of consciousness and identity throughout the tiresome and suffocating history of

LINKS:

- Russia! at the Guggenheim, New York NY

- Constructivist Criticism by Mark Stevens for New York magazine

- The" Russia!" art lovers should know by Roberta Smith for The New York Times

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home