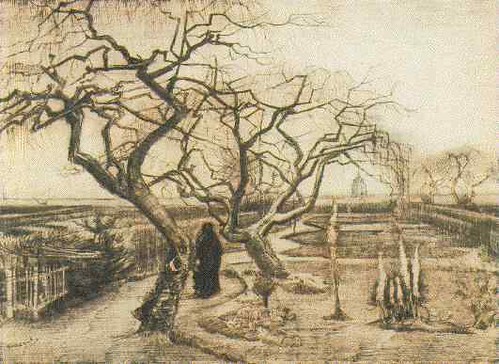

Van Gogh's Winter Garden

Vincent Van Gogh, Winter Garden, March 1884, pen and ink & graphite on paper.

The exhibition of Van Gogh’s drawings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art demonstrates the ten-year inquiry, development, and stylization of a brilliant self-taught career. While full of lively drawings with staccato line work and intense descriptions of form, a series of five earlier pieces stand out for their potency of emotion and sincerity.

Van Gogh sought to “draw as easily as writing,” which he achieved when he discovered the reed pen in Arles and ‘curlicue ciphers’ which became a speedy and effective shorthand for thoughts about light, color, shape, and perspective.

However, prior to developing this energetic style that characterized later work, Van Gogh labored extensively in the

All from March 1884 and using a deliberate language in pen and ink, these vicarage drawings possess an emotional depth, communicating Van Gogh’s fascination and intrigue with the setting. Of the Winter Garden, he wrote, “the garden sets me dreaming.” A common theme in the approach to nature at the time, this sentiment was echoed by his friend Paul Gauguin, who wrote “Art is an abstraction – derive it from nature by dreaming in its presence” in 1888. Centralizing the focus on angular bare trees stiffened by winter cold, the starkness of the flat, empty fields becomes more pronounced. The scratching, forceful quality of line work reduces the complexity of tangled branches to a graphic potency. This is particularly apparent when set against the ephemeral, atmospheric cross-hatching in the sky, which gracefully describes diffuse shifts in cold light. With a touch of the macabre Van Gogh depicts a black-cloaked peasant as a grim specter – perhaps related to the building which appears to be a church on the horizon – inflecting this image with a possible foreboding spiritual meaning befitting his Dutch Reformist upbringing.

In a second, vertical rendering of Winter Garden, Van Gogh clarified the focus and drew more precise attention to the tree with vertical sets of parallel lines flattening the ground and surrounding fields. The language in the tree is refined from thick, forceful strokes in the trunk to hair-thin tapering in the upper branches. The sophistication of mark extends to graphite used evocatively in conjunction with ink work in the sky. Together with Behind the Hedges, these two drawings are sensitive, at times slow and calm, others restless and frenzied, yet always controlled, with tight, disciplined line work and subtle tonality.

The intellectual meaning in this series becomes more explicit in Pollard Birches and The Kingfisher, drawings executed with more specific pastoral and poetic references, though perhaps slightly less of the emotional conviction of the first three.

Van Gogh wrote, “If one draws a pollard willow as if it were a living being, then the surroundings follow almost by themselves.” Ambient scribbled horizontal lines are used behind the trees in the sky and to define planes of the ground. The gnarled trees appear as thick knuckles, with a concentration of density in the whirled knots of their trunks. The deliberate, massive pollards appear particularly vital and defiant when juxtaposed with the spindly tree at the left side of the picture, whose sparse leaves contribute to the sense of merely incidental surroundings, a spring life in suspended animation.

The Kingfisher is the least immediately seductive of the set. Highlighted with chalky opaque white, the subtlety of contrast is broken in an unnatural way. When using the lightness of the paper as his highest light, Van Gogh successfully communicated a wide range of ambiance and light, but this superimposition undercuts the image as a whole. It pierces and overpowers the murkiness of the luminous sky and reflections in the river, two of the drawing’s strongest parts. Nevertheless, the drawing manages a simplicity and economy of expression in lines which become nearly abstract at the right side of the image.

These five drawings demonstrate Van Gogh’s contemplative concern for the land and its people, showing how he was “always more at ease drawing landscapes,” despite a persistent goal toward portraiture or later concern with the colors and textures of the French countryside. This series carries forward the serious demeanor of a formative artist working out basic issues of drawing, yet tackles a concise and potent metaphor rife with emotion. Dark, sincere, heartfelt, and intriguing, they feel more private and intuitive than his later sketches or presentation drawings. They are perhaps all the more potent for their self-conscious absence of the buoyancy and enthusiasm of a stylized artist recognized by his peers, giving access to a more meditative and starkly honest place in the artist’s mind.

LINKS:

- Van Gogh: the Drawings

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- NY Times multimedia presentation