Schiele's Skin

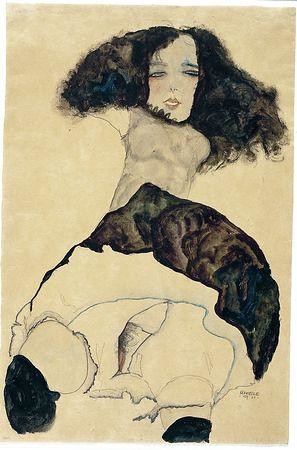

Egon Schiele, Girl with Black Hair 1911, watercolor & charcoal on paper. (left)

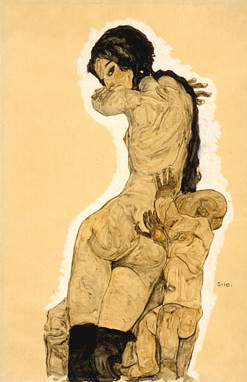

Mother and Child, 1910, watercolor & charcoal on paper (right)

To say that Egon Schiele’s show at the NEUE Galerie in

Much of Schiele’s brief career revolved around the display of skin, with allegations that his sexually-charged erotic images were indecent and obscene. In his treatment of skin’s surface qualities with a unique sensitivity to what the skin reveals, Schiele transcends the pornographic or base to create formally-stimulating, genuinely original depictions of the body and his subjects.

In his 1910 Portrait of the Painter Karl Zakovsek, Schiele uses the skin to convey exhaustion, weariness, and the strained life of a fellow artist. The redness of the eyelids and the pink tinge of Zakovsek’s lips contrast starkly with the languid pallor of his cheeks, neck and exposed chest. Hairs jut through awkwardly, intimating the rough texture his right hand meets when leaning his chin on his arm, the armrest invisible. The skin becomes more corpse-like and foreboding, as the exaggerated elongation of the left hand extends the composition to the lower right of the canvas in a vertiginous diagonal. The grey fingers point nearly straight down, the knuckles and cuticles uncomfortably rendered in exquisite detail. Zakovsek’s skin is so close in tone to his grayish-brown suit that one cannot help regarding him as a living spectre of death, despite his apparent youth as Schiele’s contemporary.

By ruthlessly overstating the world-worn translucency of Zakovsek’s skin, Schiele’s portrait is not just one of the external, but it bridges into the psychological and spiritual world of his subject, engaging the viewer into the unique situation of this sitter. By placing him as if floating in a deliberately vacant background, Schiele has defined his focus and allowed himself an opportunity to intricately explore a complex formal language, rendering flesh and fabric equally consequential as costumes of something more human underneath.

While it is the substance of Zavovsek’s skin which makes it significant, it is the blankness of his nudes that make them seductive and alluring. Particularly evident in the armless skirt-raised figure in the watercolor Girl with Black Hair from 1911 and others made for a circle of collectors of erotic art, the skin of young female nudes is marked by absence – simple charcoal lines form the contour details of anatomy, washes suggest hair or details of the fabric of her skirt. The only major marks to indicate skin quality are the flushing of the cheeks and labia, creating a blank space for projection of fantasy and evocation of the erotic without explicit participation or statement, harkening to a form of Eros associated with life-force and divine - rather than purely sexual - drives toward beauty and ecstasy. Despite Schiele’s talent to capture the very essence of character through every surface nuance, he chooses the tabula rasa of blank white thighs or an expanse of face broken with narrowed eyes, slashes for eyebrows, and rouged lips to create the illusion of innocent seduction, a woman naturally aroused for her viewer rather than the exploited child she may actually have been. It is a person reduced to a motif to allow for the highest gratification, yet preserving much of the spirit and individuality of the models in the distinction of features.

Unlike the sparsely-marked skin of his erotic nudes, a series of women drawn in an abortion clinic from 1910 explores skin in a lush, intrigued way. In Mother and Child, a rather lovely woman exposes her back, coyly turning over her left shoulder to show batting eyes and the contour of her cheek. Her black hair responds in a curved element compositionally balancing the hard lines of opaque black stockings which come mid-thigh, the figure cut off at the knees by the bottom of the paper. She seems held up or supported by the child figure, a twisted body echoing the curve of his mother’s spine, dark hands awkwardly poking in two curves below the ribs and above the pelvis. The child’s face is obscured from view and incongruously shrouded in sepia tones, which continue to his bare feet. The mother’s skin is loosely painted, following the masses of her body, at first glance appearing as fabric rather than her nudity. Her anatomy is personally specific while remaining formally generalized, the nipple on her left side forming a stylized symbol for a breast, her face seemingly a separate entity from the thick, almost grotesque fluidity of the flesh of her neck and the skin between her shoulders. By a simultaneous reductive and additive process of addressing the skin and the subject’s flowing form, Schiele releases her from judgment or misinterpretation, involving the viewer in a formal exploration charged with the peculiarity of this woman’s individual situation.

Where Schiele truly pulls no punches is in self-portraiture, perhaps the most intense and intriguing of the works in this exhibit. Two in particular stand out – Self-Portrait with Arm Twisted Above Head, 1910, and Self-Portrait with Red Eyes. Using a full-length mirror, Schiele forms a dialogue with the skin he is most familiar with, greens and sallow tones incriminating and accentuating his exaggerated features, particularly his sharply protruding ribcage. Schiele comes off as defiant and more than a bit deranged, hair raging out of his skull, wild eyes standing out sharply in contrast with the dark facial skin. His hands are the darkest, betraying indiscretions with a sense of guilt or perceived personal shortcomings, filled with the intensity and conflict of a man staring unflinching into himself. His red eyes speaks to vice, corruption, exhaustive and tireless passionate living, but with the stubbornness and impunity of youth that only the truly precocious could get away with.

Schiele presents a very modern vision of humanity at the turn of the century. In light of his dubious reputation as a pornographer or exploitative corrupter of the innocent, Schiele has created a remarkable depth of work with unique sensitivity and attenuation of detail to the most essential and viscerally significant. His work is simultaneously erotic, sexually-charged, and formally enlightened, preserving much of the dignity and grace of humanity in the face of its pathetic material reality trapped in the skin.

LINKS:

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home