Experience of Jackson Pollock's One: Number 31, 1950

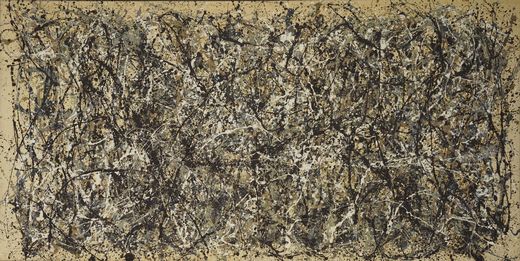

Jackson Pollock, One:Number 31, 1950. Oil and enamel on unprimed canvas. 8' 10" x 17' 5 5/8" (269.5 x 530.8 cm)

At first I approach the painting with trepidation. The way it is hung, it seems double my height and so long I cannot hold it all in view at once, except from far away. I move closer to make sense of it and find a seductive intimacy forming. I peer through the layers of paint to the pale raw canvas and feel like I am seeing skin through lace, a sensation of strange derelict contradiction. I know this piece is about paint and the way it is handled, yet I am looking through it, imagining each layer untangling from the surface and withering away. I think about what Pollock saw, looking at this fabric, and I try to visualize the dances that he did to move the paint in this way, the cadence of his steps among the first syncopated spatters, now obscured beyond identification. I wonder if he hesitated, how long he moved before pausing to examine what had been done.

I find my hand unconsciously moving from the wrist as my eyes trace the lines and drops, hearing the sounds of wet paint spraying on the ground. I follow several harder black lines to the left side, where I notice a series of verticals and arcs that make me think of leafless trees, thickets or brambles with horizontals forming branches receding in the distance, splatters making thorns. I think of grasses, fields of sorghum with pheasants hiding low, and when I turn to look down the expanse to my right, I see the rolling cascades of rivers and the ocean. I think of sand and pebbles in the current, gritty silt mixing in the paint and catching on the canvas tooth. I think of Pollock painting on the floor and begin to interpret this piece as a form of reverence, a poetic exaltation of the natural world with its simultaneous complexities and pervasive, simple order. The longer I stand looking, the more I am consumed with this painting’s order – I find myself alone in it, separate from the museum or the people around me and again feel complicit in something with it, as if I’m leaning in to hear fervent secrets whispered relentlessly.

I think about the smell of enamels and house paint, my nose instinctively wrinkling at the metallic taste in my mouth. I remember the dull headache I had for days when I first used enamels without a respirator and sigh with the memory of the breathless air in my studio. But I also remember the chemical delirium, the stink of something synthetic and fertile with possibilities.

I want to run my fingers over the smooth rivulets, feel the sleekness in the sticky-looking black, the surprising coolness. I want to feel my nails catch on the pasty white, pick at it, feel it flake off the canvas in my hands. I think of the roughness of the whole piece and again of the bare canvas like grooves between wires or stucco. The paint looks wet, but I know how hard and inflexible it would be, despite its sometimes plastic sheen.

I try to view the work again as a whole, noticing its edges and the top, trying to imagine the edges stretched around the back. In thinking about what I cannot see, I begin to sense the rhythm and undulation of the field of paint. I can’t resist the feel of a landscape, as if I’m looking through a picture window, but for the first time I see in this piece things I haven’t seen before: an interior landscape emerges, the constellations of lines forming neurons and dendritic branching, synapses in the raw spaces. I begin thinking of neurotransmitters released at the firing of action potentials and see this work as something more personal than I ever have. Pollock is transmitting – his ideas sparking and forming electric currents out of such humble materials. I imagine the white fluorescing under ultraviolet light, the painting moving toward me in hasty arcs, scribbling energies around me to construct an environment I can crawl into and move about in.

I feel like I have gotten inside.

I have always appreciated this painting historically and sense there was something special about it. This time, I felt it slip under my skin, extend a thin hand around my wrist to pull me close, and then it hissed urgently, exposing itself to me. We became allies, and I felt I finally understood it on the visceral level I require to truly love a piece of art. At that moment I realized it had stolen my breath.

LINKS:

- One: Number 31, at MoMA

- Fractal Expressionism, by Richard Taylor, Adam Micolich & David Jonas, in Physics World magazine, October 1999